How Trauma Affects the Brain and How Cognitive Fitness Can Support Focus, Memory and Emotional Regulation

- Diana T

- Nov 23

- 4 min read

Many people know trauma affects emotions, but fewer realise it can also influence how the brain processes information, stays focused, remembers and handles stress.

Research shows that trauma and prolonged stress can affect the nervous system and are associated with changes in key brain areas linked to attention, memory and emotional control.

Understanding this helps us shift from self-blame to self-compassion and toward approaches that support the brain in recovering.

How Trauma Affects the Brain

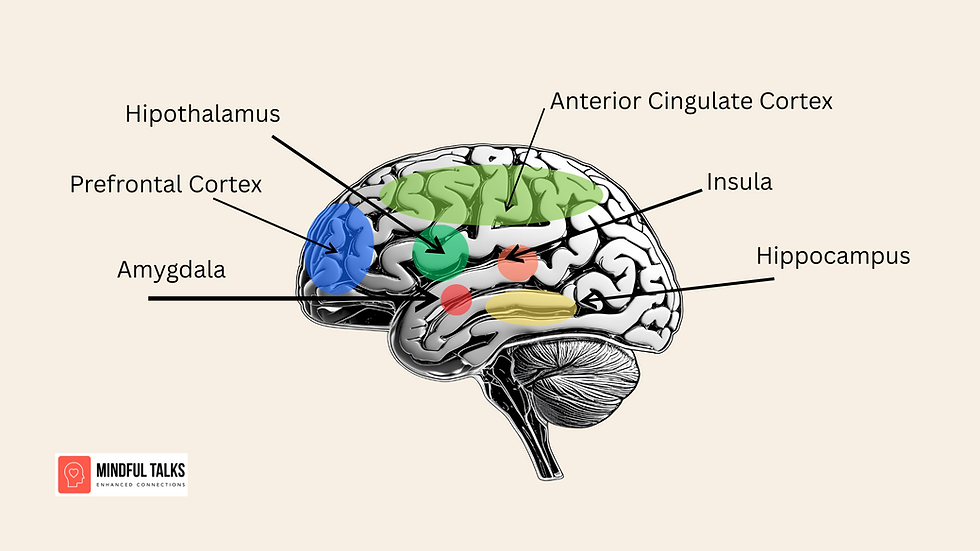

Trauma activates the body’s survival response. When this happens repeatedly or over long periods, studies show it can be associated with changes in three important brain regions:

1. The Prefrontal Cortex (focus, decision-making, self-regulation)

Research suggests that trauma and chronic stress are associated with reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex, which can make it harder to:

stay present

concentrate

follow through on tasks

organise thoughts

This is why many people say:“I know what I need to do, I just can’t seem to do it.”

2. The Hippocampus (memory, learning, clarity)

Several studies have found that people with PTSD or long-term stress may show reduced hippocampal volume, which is linked with:

forgetfulness

brain fog

difficulty retaining information

This isn’t a motivation issue, it’s a cognitive load and stress response issue.

3. The Amygdala (threat detection, emotional response)

The amygdala often becomes more reactive after trauma, which can lead to:

emotional overwhelm

irritability

anxiety

strong reactions to small triggers

This isn’t being “too sensitive”, it’s the brain trying to protect you.

The image below illustrates how trauma-related cues can activate different neural responses in adolescents, highlighting the link between stress, reward pathways and emotional processing in the brain.

Brain activation differences in response to stress, food-reward and neutral cues in adolescents with childhood trauma exposure.

Image Source: Elsey et al., Neuropsychopharmacology (2015)

Why Willpower Isn’t Enough

If the brain regions involved in focus, clarity and regulation are struggling, trying harder won’t fix it.

This is why many trauma survivors feel exhausted, easily overwhelmed, scattered or unfocused, overstimulated by noise or chaos.

'It’s not character, it’s neurobiology.'

How Cognitive Fitness Supports the Brain After Trauma

Cognitive fitness uses movement, coordination, rhythm, dual-tasking, patterning and play to activate the brain networks involved in:

attention

working memory

emotional regulation

cognitive flexibility

While research is still emerging, several studies show that physical exercise can increase neuroplasticity, cognitive training can improve executive function, brain–body approaches support regulation

This makes cognitive fitness a promising and accessible support for people who want to regain clarity, presence and emotional steadiness.

Benefits People Often Report

Many participants experience: better focus and concentration, improved emotional regulation, less overwhelm, sharper memory, more groundedness, increased confidence

Not because they “learned it”, but because their brain practiced it.

Who Can Benefit

Cognitive fitness can be beneficial for:

people affected by trauma or chronic stress

adults experiencing focus issues, brain fog or emotional reactivity

neurodivergent people, including those with ADHD or sensory overload

individuals recovering from mild brain injury or concussion (alongside medical guidance)

people with a family history of Alzheimer’s or dementia who want to support brain function proactively

expats and parents navigating overwhelm, transitions and nervous system strain

The Takeaway

If you struggle with focus, clarity, memory or emotional swings:

You are not broken.Your brain adapted to protect you.

And with the right kind of support, it can adapt again.

Join us for the next cognitive fitness workshop 'BRAIN BOOST' ⬇️

APA Reference List

Bremner, J. D. (2002). Structural changes in the brain in posttraumatic stress disorder. The Neuroscientist, 8(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858402008001001

Davis, L. L., Surís, A., & Kraus, D. (2024). The role of the amygdala in posttraumatic stress disorder: A review of neurobiological findings. Current Psychiatry Reports, 26(2), 45–59.

Erickson, K. I., Voss, M. W., Prakash, R. S., Basak, C., Szabo, A., Chaddock, L., ... & Kramer, A. F. (2011). Exercise training increases size of hippocampus and improves memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(7), 3017–3022. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1015950108

Henigsberg, N., Kalember, P., Petrović, Z. K., & Šarac, H. (2019). Neuroimaging research in posttraumatic stress disorder—focus on amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 90, 37–42.

Logue, M. W., van Rooij, S. J. H., Dennis, E. L., Davis, S. L., Hayes, J. P., Stevens, J. S., ... & Morey, R. A. (2018). Smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: A multisite ENIGMA-PGC study. Biological Psychiatry, 83(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.09.006

Samuelson, K. W., Pope, C. N., Henry, R. L., & Dvorak, L. (2020). Cognitive training for posttraumatic stress disorder and mild traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22447

Smith, M. E. (2005). Hippocampal volume and PTSD: A meta-analysis and comparison with depression. Biological Psychiatry, 57(10), 952–955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.032

Zou, L., Loprinzi, P. D., Yeung, A. S., Zeng, N., & Huang, T. (2024). The effects of exercise on neuroplasticity and brain function: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 154, 105–122.

Comments